Perhaps no medium transcends the barrier between art and science so completely as film.

When you visit the cinema, do you

ever think about the process that went into creating the film? Do you consider

the artistry of direction or the science of the camera itself? ASCUS jumped

into the deep end at the EIFF with a foray into the world of experimental cinema,

something that we found both challenging and intriguing. Eleanor Spring spoke to Kim Knowles, the curator of the Black Box

program at the EIFF, who introduced us to the process and definition of this

remarkable medium. Prepare for the extraordinary . . .

Black Box 3: Matter and Metamorphosis

The Edinburgh International Film

Festival always showcases a wide range of short films and this year was no

exception. Out of about twenty short film screenings, four were experimental

(plus one live performance) and were shown as part of the Black Box series of

programs. The films were grouped by theme: ‘(In)-action’; ‘Patterns and

Repetitions’; ‘Matter and Metamorphosis’; ‘Bodily Encounters’ and ‘Live’. It’s

intriguing that Kim Knowles, the curator of Experimental Film at the EIFF,

chose to categorise these films under titles that all included scientific

terms. Although this transpired not to have been deliberate. Knowles explained

how the film selection and categorisation process is both lengthy and

complicated, and the films themselves often inform the naming and selection of

the programs. According to their website, the first program was inspired by the

concept of action and reaction; the second by the cyclical yet unpredictable;

the third by materials, change and alchemy; the fourth by performance, ritual

and alienation. The final show was a series of live projections.

‘Black Box 3: Matter and Metamorphosis’ was of

a program of 10 highly abstract short films, 3 – 23 minutes in length. Each of the shorts focused in some way on

materials, change, or both. Apart from any scientific significance that it

might have, there’s something very poetic about the title ‘Matter and

Metamorphosis’. But what do ‘Matter’ and ‘Metamorphosis’ really mean, and how

do they relate to the films?

‘Matter’ is a tricky word. It

does not have a clear scientific definition, and can be taken to mean: mass;

particles; or any ‘thing’ at all, as long as it is not nothing! But loosely

speaking, matter is stuff, made up of particles with rest mass and volume. In

everyday terms, it tends to refer to anything solid or tangible (although

really the particles in gas are matter as well).

|

| Picture: omniology.com |

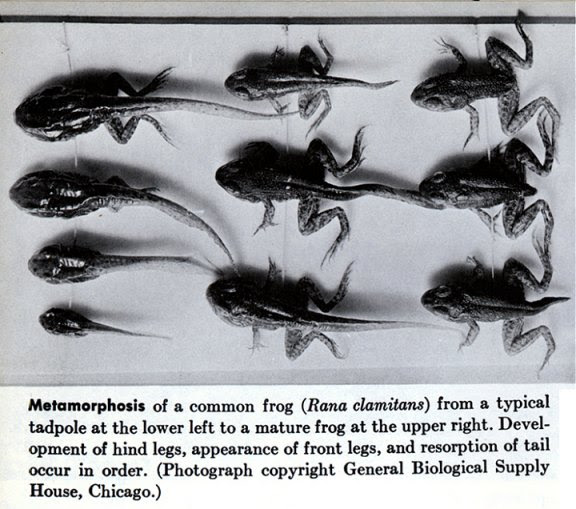

‘Metamorphosis’ is most accurately

used by biologists. It describes a rapid and distinctive change in a life form’s

physiology. A good example is the one everyone learns at school – the

transformation from frog spawn, to tadpole, and finally to frog. But again, it

is a word that crops up in everyday conversation, usually to refer to general

change and transformation.

So the program could just as

accurately (although less romantically) have been called ‘Stuff and Changes to

Stuff’. This actually gives a pretty good indication of the content of the

films in Black Box 3. Many of them were focused on some material undergoing

change – for example the dazzling ‘Crystal World’ by Pia Borg, which features

high resolution images of rapidly growing crystals, edited in with found

footage from the 1940’s Holywood movie ‘The Night of the Hunter’. However, it

was harder to see how other films sat within the theme, until Knowles revealed

that the Matter and Metamorphosis of the program title could also refer to the literal

film itself.

A recurring concept for Knowles

when selecting a program is the development of a ‘dialogue’ between analogue

and digital film. Whilst digital cinema may be unsurpassed in its visual detail

and clarity, analogue film has a tactility and warmth that cannot be fully

imitated. When analogue film is projected, the shutter on the projector has to

shut and reopen between each new image. The frame changes 24 times a second, so

the audience does not see the screen

go black, but none the less the action of the shutter lends a uniquely visceral

quality to analogue. There is also the fact that analogue film is just that –

film. It is real organic matter, and as such it offers the experimental

filmmaker a huge number of opportunities to physically experiment with the

medium. A good example is ‘Polytunnels’ by Nicky Hamlyn. To those uninitiated

to the world of experimental cinema, this is an exceptionally challenging film.

At 23 minutes in length, it was by far the longest in the program. It features

lingering black and white shots of a polytunnel farm, devoid of people,

voiceover or soundtrack. The images were often jarringly edited with flashing

lights and a flickering strobe effect. This was hard to appreciate until

Knowles explained that this effect was achieved ‘in camera’. That is, the film

images were spliced and edited in the camera during filming, not in

post-production. Hamlyn is in fact making the audience aware of the physicality

of the film itself.

To those unfamiliar with film,

and the science and artistry that contribute to its creation, the difference

between experimental cinema and the video art seen in modern galleries might be

unclear. Knowles helped explain the distinction, which might seem vague given

the fact that both forms often yield films that are both abstract and anti-narrative.

Video art tends to be an extension of a general artistic vision or theme. An

artist might have a concept that they wish to explore, and a film may end up

being part of that process. The people that view their work might just watch a

few minutes or seconds of their film, before moving on to a different part of

the gallery.

|

A still from 'Ballet Mécanique' 1923-4, considered one of the

masterpieces of early experimental cinema

Picture: Google images |

Experimental cinema, however, is the realm of filmmaker. The film

is a work in its own right. The cinema aspect means that the audience are not casual viewers, but are immersed in the film for its entirety. Experimental cinema also has its own rich history, dating back as far as the early 1920s. The films often

push the boundaries of what film the medium can do, and draw attention to the

material itself. Pere Ginard and Laura Ginès’ ‘Metamorphosis du Papillon’ features

footage of a caterpillar emerging as a butterfly from a cocoon. This natural

process is compared to the chemical change that occurs when the film itself is

burnt, resulting in a dual metamorphosis both

on film and

to the film itself, with remarkable visual effect.

Often the story behind the creation

of the film was as involving as the film itself. The first film, ‘Sou’ by

Tatsuto Kimura, was 7 minutes of almost hypnotic footage of changing textures,

colours, cracks and crumbles, without music or voiceover. Remarkably, it was

actually 7000 rapidly changing close-up colour photographs of 8 individual

rocks that Kimura had ground, washed and cracked himself in his studio, over

the course of a year.

This illustrates why so many

audiences find experimental cinema so alienating, or even aggravating. Knowles

used the analogy of a toolbox to describe an audiences’ approach to film. At

the cinema, a film is usually judged on the merits of its story, the acting,

the cinematography, the score, and the message that it means to convey. Audiences

are so used to this that they tend to approach experimental cinema with the

same outlook. Consequently, when met with a film that defies standard

interpretation, people often feel as though they are being deliberately

excluded from some deeper significance, and thus feel irritated and

underwhelmed.

So how should an audience

approach experimental cinema? It undoubtedly helps to have a little

understanding of how films are made. Maybe do a little research into the

history of cinema itself. Most importantly though is to stop looking for meaning

in the film and approach without preconception and expectation.

After all, to quote Knowles, ‘Do

we have to understand something to experience it?’ Perhaps not, but be prepared

that your experience will be unique and not necessarily conclusive.